- Home

- Leo Tolstoy

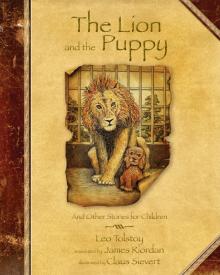

The Lion and the Puppy

The Lion and the Puppy Read online

Copyright © 1988, 2012 by Leo Tolstoy

Translation copyright © James Riordan 1988, 2012

Illustrations copyright © 1988, 2012 Claus Sievert

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written

consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries

should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifcations. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY

10018 or [email protected].

Sky Pony® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Manufactured in China, September 2011 This product conforms to CPSIA 2008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61608-484-4

CONTENTS

Introduction

Translator’s Note

The Lion and the Puppy

Little Cottontop

Escape of a Dancing Bear

Masha and the Mushrooms.

Death of a Bird-Cherry Tree

Little Philip Who Wanted to Go to School

A Young Boy’s Story of How a Storm Caught Him in the Forest

The King and the Shirt

Two Brothers Learn a Lesson

A Young Boy’s Story of How He Found Queen Bees for His Granddad

The Tired Swan

The Old Fire-Dog

Two Merchants

The Old Poplar

How Many Geese Make Six?

The “Dead” Man and the Bear

The Litde Bird

The Plum Stone

Better to Be Lean and Free than Plump and Chained

A Young Boy’s Story of How He Did Not Go to Town

Dew upon the Grass

Uncle Jacob’s Dog

Why Wolves Are Mean and Squirrels Frisky

The Ants

From an Acorn Grew an Oak Tree Tall

INTRODUCTION:

LEO TOLSTOY — STORIES FOR CHILDREN

Do you know the story of the Selfish Giant who was never visited by Spring until he opened up his garden to children? Here is a true story about a Russian nobleman who not only let children into the garden of his great country home, he also taught them to read and write. He even wrote the stories in this book for them.

And well he might. For he was one of the greatest storytellers that ever lived, a giant among authors.

His name was Leo Tolstoy.

This is how he came to write his stories for children.

Many years ago, in Russia, behind a big stone wall, there was a beautiful garden with soft green grass and glades of silver birch. The village children were not allowed into this garden. All they could see as they peered through the tall Iron railings of the gate was a distant lake shimmering through the trees beyond a neatly swept drive of stately poplars. And somewhere in the grounds of that great garden, they knew, there stood a big house in which a famous gentleman lived.

The notice on the gates said “Yasnaya Polyana,” which in Russian means “Clear Glades.”

CLEAR GLADES

Country House of Count L. N. Tolstoy

That was plain enough. The children knew they had to keep out.

How surprised — and not a little afraid — they were when one day they heard that the Count had summoned them to his mansion. The word soon spread through the village. What did he want them for? Rumor had it that he wanted to teach them to read and write.

What a strange idea!

In those days there were few enough schools in the towns, fewer still in the countryside. “Very, very rarely could a villager read or write. If a letter needed to be written, people went to the deacon and had to pay a tidy sum for it. There were no books in the village, no newspapers, no schools.

Yet now it seemed that the Count had a mind to open a school for poor children. And to teach them himself.

The children were shy But on the appointed day they put on their Sunday best — a clean shirt and fresh birch-bark shoes — smoothed down their unkempt hair with yellow sunflower oil or brown rye juice, and set off in a crowd for the Big House.

The year was 1849. The gold and russet trees of autumn had laid a crisp carpet of leaves along the drive, as the children made their way to the house. Once past the dark, still waters of the lake, a big house suddenly came into view, set back behind the trees. The tall two-story building seemed like a palace to boys and girls who had grown up in squat smoke-begrimed huts under straw-thatched roofs. Nervously, the knots of village children stood before the house, waiting for the Count to appear.

Finally he appeared on the veranda — a tall, broad-shouldered figure with long straggly hair, a large fleshy nose, and a bushy black beard. As he fixed them with his fierce stare, from under the most enormous eyebrows, the children drew back in alarm. Yet the moment he smiled and spoke, their shyness seemed to melt away

The school at Clear Glades was open all day long, and children could come and go as they pleased. No one forced them to attend, and no one forced any lessons upon them. Each child did whatever took her or his fancy — drawing, reading, writing, sports. And, by all accounts, the children came to the school very willingly, some arriving as early as seven in the morning and staying until late evening. Such was their eagerness to learn.

But it was not all sitting at desks. Tolstoy loved games. In summer he taught the children croquet on his lawn, and rigged up a small gym in the bam. He took them on nature rambles through the woods and down to the river to swim. And when the winter snows and ice came, there was no end to the games the children played: speeding downhill on great sleds, snowballing, tumbling in the snow — with the Count himself in the thick of them! They cleared the snow from the big lake to make a skating rink; they held races there, but few could beat Tolstoy, who was an excellent skater.

At Christmastime he decorated a big fir tree inside his house and held a party for all the children on his estate. Of course, the thin ragged village children had never had such a party in their lives.

In those days children’s lives were hard. As soon as they were strong enough — about the age of ten — they had to drive a wooden plow and toil in the fields from dawn to dusk. Childhood ended early in Russia at that time; peasant families were but serfs, slaves to the lords.

Yet here was a lord, Count Tolstoy, who was opening the doors of his house, with its polished wooden floors, lofty ceilings, and bright windows, to the village children. It all seemed a fairy tale.

But it was real enough. And so was their teacher’s love for them. Throughout his long life Tolstoy loved children. It hurt him to see so much poverty and ignorance among the children in the countryside. But he also knew how miserable the lives of the children in the towns were. His heart ached at the sound of the factory whistles at dawn and dusk from the mill beyond the village. He once visited that mill and wrote in his diary:

I visited a stocking mill and learned what the whistles mean. At five o’ clock in the morning a boy takes his stand beside a machine and stays there till eight. At eight he drinks tea and then stands till midday; and at one he begins again and stands till four; then he works through from half past four to eight in the evening. Every day, seven days a week. That’s what the whistles mean we hear in our beds.

He wondered how such children had time to live, children whom whistles set in motion at five in the morning and stopped at eight in the evening. When would they learn, read books, have time to play?

Tolstoy’s school was the first in Russia for village children. But when he came to seek school books that were easy to read and interesting he was disappointed. What few children’s books existed were dull and more likely to put out the spark of interest than kindle it.

So the great writer, known throughout the world for his famous books, sat down to write stories for children that were easy to read and interesting, that would teach right from wrong, good from bad. Even though his great works took up much of his time and energy, he always found time for the children.

The stories he wrote were not only for the village children around Clear Glades. They were intended for all girls and boys who wish to open up their hearts to truth and beauty.

TRANSLATORS NOTE

The stories are taken from Tolstoy’s Azbuka (Primer) which consisted of four “Russian Reading Books,” four “Slav Reading Books,” a section on teaching reading, handwriting, and arithmetic, and guidance for teachers. Although the Primer was not published until 1872, it was based on notebooks Tolstoy had kept from his first teaching experience at his school for peasant children at Yasnaya Polyana (Clear Glades) from 1849 and at other schools he founded for peasant children in the Tula Province.

The stories vary widely: some are based on Aesop’s fables, others on Russian and foreign folk tales, some on nature studies, and others on the work of children themselves. As an example of the latter, the “Young Boy’s Stories” all come from the storytelling of peasant children whom Tolstoy encouraged to read and write “in their own words.“

What distinguishes all the stories in the Primer from children’s stories current in Russian schools at that time is that they are largely free from the heavy moralistic homilies and religious preaching that Tolstoy abhorred. Moreover, they are written in a simple language style “for a new audience,” as Tolstoy put it, “that has to be counted in many thousands, even millions“

The present versions are taken from Novaya azbuka (New Primer) and the four Russkie knigi dlya chteniya (Russian Reading Books) edited by Tolstoy for the 1875 edition. They are contained in L. N. Tolstoy Sobranie sochineniy v 14 tomkakh, torn desyaty (Collected Works in 14 Vol-u mes, vol 10), Moscow, 1952.

THE LION AND THE PUPPY

There was once a zoo in London that took stray cats and dogs to feed its wild animals. One time, a visitor to the zoo picked up a puppy from the street and took it along with him. Handing it over at the gate, he watched the keeper throw the hapless puppy into the lion’s cage.

Poor little dog.

Tail between its legs, it squeezed itself into the corner of the cage as the lion came closer and closer.

Suddenly the lion stopped and began to sniff his victim. Tickled by the lion’s whiskers, the puppy rolled over and wagged its tail playfully At that, the lion prodded it uncertainly with his paw, pushing it to and fro over the floor of his cage.

To the lion’s surprise, the little dog nimbly jumped up and stood on its hind legs, begging.

Puzzled, the lion stared at the dog, shifting his massive head slowly from side to side, not knowing what to make of this funny little animal.

But he let it be.

At feeding time, when the keeper tossed meat into the cage, the lion tore off a piece for the puppy And at sunset, as the lion lay down to sleep, the puppy lay alongside him, resting its tiny head on the lion’s great paws.

From that day on the lion and the puppy lived together in the same cage: the lion sharing his food, never harming his companion, sleeping alongside and, now and then, playing with it.

Then, one day, a fine gentleman visited the zoo and straightaway recognized his long-lost pet. The keeper was informed and, of course, would willingly have handed it over had not the lion raged and roared every time he approached the puppy in the end he gave up and the gentleman had to go home empty-handed.

So the lion and the puppy stayed together; thus it continued for a whole year, until one day the little dog fell sick. And in a short space of time it died.

What a change came over the lion! All the while he licked and sniffed his friend, prodding it with his paw. At last, realizing it was indeed dead, the lion sprang up, his mane quivering with rage. He stalked about the cage, swinging his tail fiercely He flung himself against the iron bars and tore at the wooden floorboards.

All day long he roared in his anguish until finally he sank down beside his dead companion. And he was quiet.

But when the keeper tried to remove the dead puppy, the lion growled menacingly and would not let him near. After a while, the keeper had an idea. Thinking a new puppy would make the lion forget his grief, he thrust another dog between the bars.

But the lion ignored the puppy.

Then, gently, he put his paws about his cold little friend and lay grieving for a full five days.

And on the sixth day the lion died.

LITTLE COTTONTOP

There was once an old man and old woman. One day the old man went off to the fields to plow, while the old woman stayed home to make pancakes. When the pancakes were ready, she said to herself:

“If only we had a son to take some pancakes to his father.”

All of a sudden, a little boy popped out of a pile of cotton, piping, “Hello there, Mummy!”

What a fright he gave the old woman.

“Where did you spring from, Sonny? What’s your name?”

Said the lad in reply, “You spun some cotton, Mummy, and left it in the frame. That’s where I hatched out. My name is Little Cottontop. Now give me the pancakes and I’ll take mem to Daddy”

Once more she was surprised.

“you will take them, Cottontop?”

“Sure I will.”

So the old woman wrapped the pancakes into a bundle and gave them to the little boy. Little Cottontop took the bundle and ran with it over his shoulder to the fields.

As he crossed the field he found his way barred by a clod of earth.

“Daddy, Daddy,” he called. “Help me over the clod of earth! I’ve brought you some pancakes.”

The old man could hear someone calling him, and as he went toward the sound he suddenly saw the little fellow, no bigger than a clod of earth.

“Where did you spring from, Sonny?” he asked.

“I hatched out of a pile of cotton, Daddy,” he said, handing him the pancakes.

As he sat down to eat, he heard the boy call, “Hey, Daddy, can I try plowing?”

The old man shook his head. “You won’t have the strength,” he said.

But Little Cottontop took hold of the plow and began to till the field, singing as he went.

Meantime, a wealthy gentleman was passing by and saw the old man sitting at his meal, with his horse plowing on its own. So the gentleman stepped down from his carriage and called to the old man:

“How do you get your horse to plow by itself?”

“That’s my son plowing,” answered the old man. “That’s him singing, too.”

At that the gentleman came closer, heard the singing, and caught a glimpse of Little Cottontop.

“Good gracious,” he exclaimed. “Sell that lad to me, old fellow?”

But the old man shook his head. “No, I cannot, he’s all I have.”

But Cottontop whispered in his ear, “Go on, Daddy, I’ll run away from him.”

So the poor peasant sold the boy for a hundred rubles. The gentleman handed over the money, took the lad, wrapped him in a handkerchief, and put him into his pocket. When he arrived home he said, to his wife:

“I’ve a big surprise for you, my dear.“

“Oh, do show it to me,” she said in delight.

The gentleman pulled the handkerchief from his pocket and unwrapped it, but there was nothing there. Little Cottontop had run back to his father.

ESCA

PE OF

A DANCING BEAR

When I was a boy some men hereabouts used to catch bear cubs and teach them to dance. Then, when they grew older, the bears were dressed up and taken round the fairs. It was the custom for one person to lead the bear, while the other would dress up as a goat and beat a drum.

One such party was once on its way to a fair at Novgorod, a young boy in goatskin leading the way and banging a drum. As was usual for the Novgorod spring fair, the town was packed with visitors from all over Russia and the dancing bear drew much attention, earning his master a tidy sum of money.

At the end of the day, the master, the boy, and the dancing bear made their way to an inn where they gave a last show in the yard. This time they received plenty of wine in reward. The master gratefully gulped down his wine, giving some to the boy and a whole dishful to Old Bruno the Bear.

At nightfall, the party had to spend the night in a field beyond the town. The master tied the bear’s chain around his own waist, as he stretched out on the ground to sleep. Being somewhat tired and tipsy, he was soon snoring contentedly; so, too, was the boy, his assistant. Thus the two slumbered on soundly until daybreak.

When the master awoke, he found to his alarm that the bear was missing. Rousing his assistant, he rushed off in search of the runaway bear. The grass being high, they could plainly see the bear’s tracks leading into the forest. They realized that it would be almost impossible to catch the bear once he reached the shelter of the woods.

The boy was all for giving up the chase, but the old man was stubborn.

“That bear’s our living, lad,” he said. “It took five years to train him. If we don’t find him we’re dead broke — worse than beggars. No, I’ll find that brown villain yet!”

On they went into the trees until, toward dusk, they came to a broad meadow. Just as they sank down to rest, the sounds of a chain clanking nearby brought them quickly to their feet; and they stole cautiously toward the noise.

There in a clearing was the bear: the poor old fellow was shuffling along, pulling the chain and, with his paws, trying to tear the wicked muzzle from his snout. As soon as he spotted his old master, he gave a fearful roar and bared his yellow teeth. The boy was frightened and would have fled had not his master pulled him after the bear.

The Death of Ivan Ilych

The Death of Ivan Ilych Anna Karenina

Anna Karenina Resurrection

Resurrection Family Happiness

Family Happiness War and Peace

War and Peace The Cossacks

The Cossacks The Kreutzer Sonata

The Kreutzer Sonata A Confession

A Confession The Kingdom of God Is Within You

The Kingdom of God Is Within You Father Sergius

Father Sergius Childhood, Boyhood, Youth

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth Lives and Deaths

Lives and Deaths The Devil

The Devil The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Master and Man

The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Master and Man The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy (25+ Works with active table of contents)

The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy (25+ Works with active table of contents) Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (Penguin ed.)

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (Penguin ed.) The Power of Darkness

The Power of Darkness Android Karenina

Android Karenina Family Happiness and Other Stories

Family Happiness and Other Stories The Lion and the Puppy

The Lion and the Puppy Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 2

Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 2 Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 1

Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 1