- Home

- Leo Tolstoy

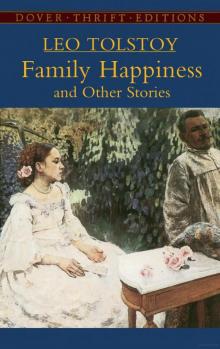

Family Happiness and Other Stories

Family Happiness and Other Stories Read online

DOVER THRIFT EDITIONS

GENERAL EDITOR: MARY CAROLYN WALDREP

EDITOR OF THIS VOLUME: T. N. R. ROGERS

Copyright

Copyright © 2005 by Dover Publications, Inc. All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2005, is a new compilation of six unabridged stories, reprinted from standard editions: “Family Happiness” (Cee , 1859), “Three Deaths” (, , 1859), “The Three Hermits” ( , 1886), “The Devil”o, writen 1889–1890; first published 1911), “Father Sergius” (O C,written 1890-1898; first published 1911), and “Master and Man” ( pa, 1895). Spelling has been made consistent and Americanized, and the editor has written a new Introduction and a few footnotes specially for the Dover edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tolstoy Leo, graf, 1828-1910.

[Short stories. English. Selections]

Family happiness and other stories / Leo Tolstoy.

p. cm. - (Dover thrift editions)

1st work originally published: 1859. 2nd work originally published: 1859. 3rd word originally published: 1886. 4th work originally published: 1911. 5th work originally published: 1911. 6th work originally published: 1895. With new introd.

Contents: Family happiness—Three deaths—The three hermits—The devil—Father Sergius—Master and man.

9780486112305

1. Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 1828-1910-Translations into English. I. Title. II. Series.

PG3366.A13 2005

891.73’3—dc22

2005045420

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

Introduction

LEV NIKOLAYEVICH TOLSTOY (1828–1910) will of course always be best known for War and Peace and Anna Karenina. But before and after those monumental novels, he produced many short stories, essays, and short novels (or long stories—a particularly Russian form known as povesti). This volume, which contains four of his long stories and two shorter ones, spans almost his entire writing life and displays well his unique, uneasy temperament and intelligence.

“Family Happiness,” the longest, richest, and most novelistic (though not the most powerful) of the stories presented here, comes from his early period—the period, that is, before his marriage and before his great novels. As he does in much of his best fiction, Tolstoy makes substantial use of the facts of his life—especially those that have left him wracked with guilt. In 1856, after the death of her father, he was appointed the tutor to a young woman named Valeriya Arseneva, who lived on a nearby estate. He became deeply involved with her, but could not bring himself to marry her. “I never loved her with real love,” he admitted later. “I was carried away by the reprehensible desire to inspire love. This gave me a delight I had never before experienced.... I have behaved very badly.”1 His impeccable artistry and sensitivity led him to imagine the story from the point of view of the young woman, and thus it took on its own life, its own truth. But the bad behavior continued to haunt him; after the story was done and was set to be published, he wrote to a friend that it was a vile, loathsome work, and begged him to burn the manuscript.

At that time, still unmarried, he had not yet personally experienced the tortuous ups and downs of family happiness. He married only a few years later, in 1862, when he was thirty-four. His bride was the eighteen-year-old Sofya Andreyevna Bers, with whom he would live almost fifty years and who would bear thirteen of his children. Because he wanted their relationship to be completely honest, he invited her to read his diaries before their wedding. Such a dose of the truth was more than she really wanted. She was in love, and was able, she thought, to forgive Tolstoy his past affairs—but his diaries made them so vivid that they festered in her all the rest of her life.

The hardest to deal with were his fevered words about a married young peasant woman named Aksinya, who had borne him a son and with whom he had had a deep, passionate affair till two years before his marriage. That affair was part of the genesis of “The Devil.” But according to Aylmer Maude, Tolstoy’s friend and translator, the story was also based on an incident from 1880, when Tolstoy asked a tutor at Yasnaya Polyana, his estate, to accompany him on his daily walks to keep him from acting on a temptation. As he confessed to the tutor, he had arranged an assignation with the servants’ cook, which had only been prevented when one of his children called out to him as he was setting out to meet her. Tolstoy’s daughter Aleksandra said that he had dashed off a draft of “The Devil” in the fall of 1889 and then put it aside for twenty years before revising it.2 He kept it hidden from Sofya in order to keep her jealousy of Aksinya, which had never ceased to torment her, from flaring up again.

Right up to the end, “The Devil” is vital, genuine, and impassioned—“real,” as Mark Van Doren says, “in the same awful way in which Tolstoi at his best was always real—and in a way that the term ‘realism,’ incidentally, cannot illuminate.”3 It is well worth reading, but the ending—or lack of one—is a terrible disappointment. Tolstoy wrote two different endings, both of which are included here, but neither fits well with what has gone before, and it is unlikely that either was satisfying to him. And that is certainly at least one reason why the story was not published till after his death.

Another of the stories not published till after his death was “Father Sergius.” In the late 1870s Tolstoy had gone through a spiritual crisis (detailed in A Confession, 1882) that had left him almost suicidal and had led him to embrace a Christianity of self-denial. In his earlier fiction, he had approached the world with artistry and an open mind. In his later work the artistry is still there, but it is sometimes at war with the spiritual message he wants to convey. As in most of Tolstoy’s fiction, the twists and turns of “Father Sergius” are as unpredictable as those of life. But once again the ending feels forced.

Some literary historians have suggested that Tolstoy avoided publishing “Father Sergius” and several other stories in order to minimize friction with his wife. It’s true that he had given up the copyrights of all of his later work, and that Sofya disagreed with this decision, as she disagreed with so much of the way he was living. So perhaps it was because he wanted to avoid quarreling with her about publication rights that he did not publish “Father Sergius” or “The Devil.” But it also seems likely that he wasn’t completely satisfied with them.

Tolstoy was, after all, his own harshest critic. Even when he felt good about his work, he often remained uncertain about whether it was worth publishing. For instance, when he had finished “Master and Man”4—the most powerful of the stories included here—Tolstoy needed to be reassured, and sent the manuscript to a friend, saying “It is so long since I’ve written anything artistic that I truly do not know whether it ought to be printed.” “My God!” his friend wrote back, “how splendid, priceless it is . . .”5 His friend was right. It may have been Tolstoy’s religious beliefs that moved him to write the story, but the story remains deeply human and moving in every detail. And yes—priceless.

The remaining two stories are much shorter, and both are charming and unusual. The first, “Three Deaths,” is from his early period. He wrote it long before his spiritual crisis and conversion, and it has almost a Taoist feeling. This is what he had to say about it in a letter to his cousin Alexandra before the story was published:

My idea was this: three creatures died . . . . [One] is pitiful and loathsome because she has lied all her life, and lies when on the point of death.... [Another] dies peacefully just because he is not a Christian. His religion is different, even though by force of habit he has observed the

Christian ritual: his religion is nature, which he has lived with.... [The third] dies peacefully, honestly, and beautifully. Beautifully—because it doesn’t lie, doesn’t put on airs, isn’t afraid, and has no regrets. There you have my idea, and of course you don’t agree with it; but it can’t be disputed—it is in my soul, and in yours too.6

The other, “The Three Hermits,” from almost three decades later, is one of a group of stories Tolstoy took from folk tales. A decade or so later, in What Is Art? (1897), he gave his opinion that such folk art—tales or jokes that might delight millions of people—was much more valuable than novels written for the bored delectation of the leisured classes. According to his son Ilya, Tolstoy heard many such tales from a wandering minstrel named Shchegolenkov, who stayed with them in the summer of 1879:

His endless stories delighted me and I loved to sit and gaze at his long gray beard, which hung in twisted locks. These tales were imbued with remote antiquity, and one felt in them the accumulation of centuries of sound wisdom. Papa used to listen to him with great interest, every day making him recite something new, and Petrovich never failed to comply. He was inexhaustible. Later Father borrowed several of these subjects for his popular tales.7

So “The Three Hermits” might be called “found art.” What makes it Tolstoy’s is its neat illustration of one of his core beliefs: that the poor and the unlearned are the natural children of God. Most of the stories in this book are enriched by that philosophy.

T. N. R. ROGERS

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introduction

Family Happiness

Three Deaths

The Three Hermits

The Devil

Father Sergius

Master and Man

Family Happiness

PART I

Chapter I

WE were in mourning for my mother, who had died in the autumn, and I spent all that winter alone in the country with Katya and Sonya.

Katya was an old friend of the family, our governess who had brought us all up, and I had known and loved her since my earliest recollections. Sonya was my younger sister. It was a dark and sad winter which we spent in our old house of Pokrovskoye. The weather was cold and so windy that the snowdrifts came higher than the windows; the panes were almost always dimmed by frost, and we seldom walked or drove anywhere throughout the winter. Our visitors were few, and those who came brought no addition of cheerfulness or happiness to the household. They all wore sad faces and spoke low, as if they were afraid of waking someone; they never laughed, but sighed and often shed tears as they looked at me and especially at little Sonya in her black frock. The feeling of death clung to the house; the air was still filled with the grief and horror of death. My mother’s room was kept locked; and whenever I passed it on my way to bed, I felt a strange uncomfortable impulse to look into that cold empty room.

I was then seventeen; and in the very year of her death my mother was intending to move to Petersburg, in order to take me into society. The loss of my mother was a great grief to me; but I must confess to another feeling behind that grief—a feeling that though I was young and pretty (so everybody told me), I was wasting a second winter in the solitude of the country. Before the winter ended, this sense of dejection, solitude, and simple boredom increased to such an extent that I refused to leave my room or open the piano or take up a book. When Katya urged me to find some occupation, I said that I did not feel able for it; but in my heart I said, “What is the good of it? What is the good of doing anything, when the best part of my life is being wasted like this?” And to this question, tears were my only answer.

I was told that I was growing thin and losing my looks; but even this failed to interest me. What did it matter? For whom? I felt that my whole life was bound to go on in the same solitude and helpless dreariness, from which I had myself no strength and even no wish to escape. Towards the end of winter Katya became anxious about me and determined to make an effort to take me abroad. But money was needed for this, and we hardly knew how our affairs stood after my mother’s death. Our guardian, who was to come and clear up our position, was expected every day.

In March he arrived.

“Well, thank God!” Katya said to me one day, when I was walking up and down the room like a shadow, without occupation, without a thought, and without a wish. “Sergey Mikhaylych has arrived; he has sent to inquire about us and means to come here for dinner. You must rouse yourself, dear Mashechka,” she added, “or what will he think of you? He was so fond of you all.”

Sergey Mikhaylych was our near neighbor, and, though a much younger man, had been a friend of my father’s. His coming was likely to change our plans and to make it possible to leave the country; and also I had grown up in the habit of love and regard for him; and when Katya begged me to rouse myself, she guessed rightly that it would give me especial pain to show to disadvantage before him, more than before any other of our friends. Like everyone in the house, from Katya and his goddaughter Sonya down to the helper in the stables, I loved him from old habit; and also he had a special significance for me, owing to a remark which my mother had once made in my presence. “I should like you to marry a man like him,” she said. At the time this seemed to me strange and even unpleasant. My ideal husband was quite different: he was to be thin, pale, and sad; and Sergey Mikhaylych was middle-aged, tall, robust, and always, as it seemed to me, in good spirits. But still my mother’s words stuck in my head; and even six years before this time, when I was eleven, and he still said “thou” to me, and played with me, and called me by the pet-name of “violet”—even then I sometimes asked myself in a fright, “What shall I do, if he suddenly wants to marry me?”

Before our dinner, to which Katya made an addition of sweets and a dish of spinach, Sergey Mikhaylych arrived. From the window I watched him drive up to the house in a small sleigh; but as soon as it turned the corner, I hastened to the drawing room, meaning to pretend that his visit was a complete surprise. But when I heard his tramp and loud voice and Katya’s footsteps in the hall, I lost patience and went to meet him myself. He was holding Katya’s hand, talking loud, and smiling. When he saw me, he stopped and looked at me for a time without bowing. I was uncomfortable and felt myself blushing.

“Can this be really you?” he said in his plain decisive way, walking towards me with his arms apart. “Is so great a change possible? How grown-up you are! I used to call you ‘violet,’ but now you are a rose in full bloom!”

He took my hand in his own large hand and pressed it so hard that it almost hurt. Expecting him to kiss my hand, I bent towards him, but he only pressed it again and looked straight into my eyes with the old firmness and cheerfulness in his face.

It was six years since I had seen him last. He was much changed—older and darker in complexion; and he now wore whiskers which did not become him at all; but much remained the same—his simple manner, the large features of his honest open face, his bright intelligent eyes, his friendly, almost boyish, smile.

Five minutes later he had ceased to be a visitor and had become the friend of us all, even of the servants, whose visible eagerness to wait on him proved their pleasure at his arrival.

He behaved quite unlike the neighbors who had visited us after my mother’s death. They had thought it necessary to be silent when they sat with us, and to shed tears. He, on the contrary, was cheerful and talkative, and said not a word about my mother, so that this indifference seemed strange to me at first and even improper on the part of so close a friend. But I understood later that what seemed indifference was sincerity, and I felt grateful for it. In the evening Katya poured out tea, sitting in her old place in the drawing room, where she used to sit in my mother’s lifetime; Sonya and I sat near him; our old butler Grigori had hunted out one of my father’s pipes and brought it to him; and he began to walk up and down the room as he used to do in past days.

“How many terrible changes the

re are in this house, when one thinks of it all!” he said, stopping in his walk.

“Yes,” said Katya with a sigh; and then she put the lid on the samovar and looked at him, quite ready to burst out crying.

“I suppose you remember your father?” he said, turning to me.

“Not clearly,” I answered.

“How happy you would have been together now!” he added in a low voice, looking thoughtfully at my face above the eyes. “I was very fond of him,” he added in a still lower tone, and it seemed to me that his eyes were shining more than usual.

“And now God has taken her too!” said Katya; and at once she laid her napkin on the teapot, took out her handkerchief, and began to cry.

“Yes, the changes in this house are terrible,” he repeated, turning away. “Sonya, show me your toys,” he added after a little and went off to the parlor. When he had gone, I looked at Katya with eyes full of tears.

“What a splendid friend he is!” she said. And, though he was no relation, I did really feel a kind of warmth and comfort in the sympathy of this good man.

I could hear him moving about in the parlor with Sonya, and the sound of her high childish voice. I sent tea to him there; and I heard him sit down at the piano and strike the keys with Sonya’s little hands.

Then his voice came—“Marya Aleksandrovna, come here and play something.”

I liked his easy behavior to me and his friendly tone of command; I got up and went to him.

“Play this,” he said, opening a book of Beethoven’s music at the adagio of the “Moonlight Sonata.” “Let me hear how you play,” he added, and went off to a corner of the room, carrying his cup with him.

The Death of Ivan Ilych

The Death of Ivan Ilych Anna Karenina

Anna Karenina Resurrection

Resurrection Family Happiness

Family Happiness War and Peace

War and Peace The Cossacks

The Cossacks The Kreutzer Sonata

The Kreutzer Sonata A Confession

A Confession The Kingdom of God Is Within You

The Kingdom of God Is Within You Father Sergius

Father Sergius Childhood, Boyhood, Youth

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth Lives and Deaths

Lives and Deaths The Devil

The Devil The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Master and Man

The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Master and Man The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy (25+ Works with active table of contents)

The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy (25+ Works with active table of contents) Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (Penguin ed.)

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (Penguin ed.) The Power of Darkness

The Power of Darkness Android Karenina

Android Karenina Family Happiness and Other Stories

Family Happiness and Other Stories The Lion and the Puppy

The Lion and the Puppy Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 2

Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 2 Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 1

Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 1