- Home

- Leo Tolstoy

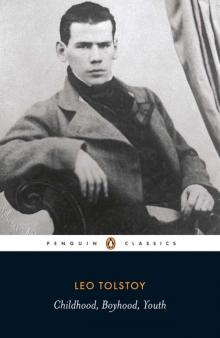

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (Penguin ed.)

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (Penguin ed.) Read online

LEO TOLSTOY

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth

Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by JUDSON ROSENGRANT

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

Chronology

Introduction

Further Reading

Note on the Text and Translation

Note on Names, Languages and Transliteration

List of Characters

Childhood

1 Our Teacher, Karl Ivanych

2 Maman

3 Papa

4 Lessons

5 The Holy Fool

6 Preparations for the Hunt

7 The Hunt

8 Games

9 Something Like First Love

10 What Kind of Man Was My Father?

11 Activities in the Study and Drawing Room

12 Grisha

13 Natalya Savishna

14 Parting

15 Childhood

16 Verses

17 Princess Kornakova

18 Prince Ivan Ivanych

19 The Ivins

20 Company Arrives

21 Before the Mazurka

22 The Mazurka

23 After the Mazurka

24 In Bed

25 A Letter

26 What Awaited Us in the Country

27 Grief

28 Last Sad Memories

Boyhood

1 A Trip in Stages

2 A Thunderstorm

3 A New View

4 In Moscow

5 My Older Brother

6 Masha

7 Shot

8 Karl Ivanych’s Story

9 The Preceding Continued

10 Further

11 A Low Mark

12 A Little Key

13 The Deceiver

14 A Temporary Derangement

15 Daydreams

16 It Will All Work Out in the End

17 Hatred

18 The Maids’ Room

19 Boyhood

20 Volodya

21 Katenka and Lyubochka

22 Papa

23 Grandmother

24 Me

25 Volodya’s Friends

26 Discussions

27 The Start of a Friendship

Youth

1 What I Consider the Beginning of Youth

2 Spring

3 Daydreams

4 Our Family Circle

5 Rules

6 Confession

7 My Trip to the Monastery

8 My Second Confession

9 How I Prepared for My Examination

10 The History Examination

11 The Mathematics Examination

12 The Latin Examination

13 I’m a Grown-up

14 What Volodya and Dubkov Were Doing

15 I Am Feted

16 A Quarrel

17 I Get Ready to Make Some Calls

18 The Valakhins

19 The Kornakovs

20 The Ivins

21 Prince Ivan Ivanych

22 A Heart-to-Heart Talk with My Friend

23 The Nekhlyudovs

24 Love

25 I Get Acquainted

26 I Show Off My Best Side

27 Dmitry

28 In the Country

29 Our Relationship with the Girls

30 My Occupations

31 Comme il faut

32 Youth

33 Our Neighbours

34 Father’s Marriage

35 How We Took the News

36 The University

37 Matters of the Heart

38 Society

39 A Carousal

40 My Friendship with the Nekhlyudovs

41 My Friendship with Nekhlyudov

42 Our Stepmother

43 New Comrades

44 Zukhin and Semyonov

45 I Fail

Notes

PENGUIN CLASSICS

CHILDHOOD, BOYHOOD, YOUTH

LEO TOLSTOY was born in 1828 at Yasnaya Polyana, his family estate near the city of Tula, 125 miles south of Moscow. He was educated there and in Moscow by private tutors before entering the University of Kazan in 1844, first in the Department of Arabo-Turkic Languages in preparation for a diplomatic career, and then in the Department of Jurisprudence. He withdrew from the university in his third year to return to his estate, intending to devote himself to its management and to independent study. Soon losing interest in those projects, he gave himself up to dissipation and gambling in Tula and then in Moscow and St Petersburg, before joining his oldest brother in the Caucasus in 1851 to seek a career in the army. He also began to write at that time, publishing his first work of fiction, Childhood (1852), and quickly following it with Boyhood (1854) and his Sevastopol Sketches (1855–6), the latter based on his experience as a front-line artillery officer in the Crimean War. Resigning his commission in 1856, he returned to Yasnaya Polyana to concentrate on the management of the estate and his writing, publishing Youth in 1857. In 1862 he married the much younger Sofya Behrs. They would have thirteen children, as Tolstoy continued to attend to his estate, the innovative school for peasant children he established there and his writing, producing, among many other important works, The Cossacks (1863), War and Peace (1865–9), Anna Karenina (1875–8), A Confession (1884), The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), The Kreutzer Sonata (1889) and Resurrection (1899). A Confession marked a spiritual crisis in his life, leading to a repudiation of church and state, an indictment of the weakness of the flesh and a denunciation of private property. His teachings brought him many followers at home and abroad, but also official disfavour and harassment, and in 1901 he was excommunicated by the Russian Orthodox Church. He died in 1910 at the small railway station of Astapovo during a dramatic flight from home, having become not only one of the world’s greatest writers but also one of its most famous men.

JUDSON ROSENGRANT has translated and edited a wide variety of Russian literature and historiography, including works by Yury Olesha, Andrei Platonov, Lydia Ginzburg, Fazil Iskander, Edward Limonov and Edvard Radzinsky. He received his PhD in Slavic Languages and Literature from Stanford University with a dissertation on Vladimir Nabokov, and has taught Russian language, literature and culture at the University of Southern California, Indiana University and Reed College in the United States, and translation theory and practice at St Petersburg State University in Russia. He lives in Portland, Oregon, USA.

Chronology

1828 9 September (28 August, Old Style). Birth of Count Leo (Lev) Tolstoy, the fourth son of Count Nikolay Tolstoy and Princess Marya Volkonskaya, at Yasnaya Polyana (Clear Glade), their estate 125 miles south of Moscow near the city of Tula.

1830 Death of mother a few months after the birth of her daughter, Marya.

1837 Death of father not long after the five children move from Yasnaya Polyana to continue their education in Moscow in the home of their paternal grandmother.

1838 Death of grandmother. The two oldest children, Nikolay and Sergey, move to the home of their father’s older sister, Alexandra

Osten-Sacken, to continue their Moscow studies, while Dmitry, Leo and Marya return to Yasnaya Polyana and the care of Leo’s beloved ‘Auntie’ Tatyana Yergolskaya, their father’s second cousin and the person who Leo would later say had the greatest and most beneficial influence on him.

1841 Death of Aunt Alexandra. All five children move to the Volga city of Kazan and the home of their father’s younger sister, Pelageya Yushkova.

1844 Already a fine linguist with an excellent knowledge of French and German and a good command of English, thanks to his home education and gifts, he enters the University of Kazan in the Department of Arabo-Turkic Languages, the country’s best, to study Turkish and Tatar in preparation for a diplomatic career. The year, however, is squandered in drinking, gambling and regular visits to brothels.

1845 After failing his year-end examinations in the Department of Arabo-Turkic Languages, he enrols in the Department of Jurisprudence, where he works with the brilliant young professor of civil law Dmitry Meier. Meier encourages him to make a close study of Montesquieu (De l’esprit des lois) in relation to the Instruction (Nakaz) of Catherine II.

1847 Inherits Yasnaya Polyana in the final distribution of his father’s property. Recovering from gonorrhoea, leaves the university for Yasnaya Polyana on the grounds of ‘ill-health and domestic circumstances’ to pursue his own programme of enlightened estate management, self-improvement and reading, including the complete works of Rousseau.

1848 Leaves Yasnaya Polyana for Moscow, where he engages in dissipation and gambling, incurring large debts.

1849 Goes to St Petersburg, where he decides to take the examinations at the university in the Department of Jurisprudence with the goal of entering government service. Passes the examinations in criminal and civil law, but again lapses into dissipation and gambling, acquiring further debts.

1850 Returns to Yasnaya Polyana, where, determined to put his life in order, he undertakes a serious study of music and once again devotes himself to the management of his estate.

1851 Begins his first literary effort, the soon abandoned ‘Story of Yesterday’. Travels to the Caucasus with oldest brother Nikolay, an officer in an artillery brigade. While billeted in a Cossack village on the border of Chechnya and resolving to earn his own commission as a cadet-volunteer or yunker involved in actions against the Chechen tribesmen, works on an unfinished translation of Laurence Sterne’s Sentimental Journey and on Childhood, his first completed work of fiction.

1852 Childhood published by the poet Nikolay Nekrasov in his influential literary monthly The Contemporary. It is very warmly received by the leading writers of the day, including Ivan Turgenev and the influential critic Pavel Annenkov.

1853 ‘The Raid’, an account based on his own Caucasian military experience, is published in The Contemporary.

1854 Receives his commission and after the start of the Crimean War is transferred at his own request to Sevastopol, where he commands a front-line artillery battery in the unsuccessful defence of the port city. Boyhood is published in The Contemporary and is received even more warmly than Childhood.

1855 Gains further celebrity with the publication in The Contemporary of the first two of the three Sevastopol Sketches, his powerful, brutally realistic treatments of the war. Travels to St Petersburg on army business, where he meets Nekrasov and the staff of The Contemporary and makes the acquaintance of the writers in its orbit, including Turgenev, Ivan Goncharov, Alexander Druzhinin, Alexander Ostrovsky, Fyodor Tyutchev, Afanasy Fet and Nikolay Chernyshevsky.

1856 The third of the Sevastopol Sketches is published in The Contemporary, as are the stories ‘The Snowstorm’ and ‘Two Hussars’. Later that year the long story ‘A Landowner’s Morning’ appears in Patriotic Annals. Resigns his commission and returns to Yasnaya Polyana. Tries unsuccessfully to free the peasants of his estate from serfdom. Death of his brother Dmitry from tuberculosis.

1857 Makes his first trip abroad, a six-month visit to Switzerland, France, Germany and Italy. Sees Turgenev in Paris. Youth, the last and longest of his three accounts of pychological and social development, is published in The Contemporary, as is his story ‘Lucerne’, written in Switzerland.

1858 Back at Yasnaya Polyana, devotes himself to his literary work and the estate.

1859 The story ‘Three Deaths’ is published in The Library for Reading and the short novel Family Happiness in The Russian Herald. Starts an innovative school for peasant children at Yasnaya Polyana, an endeavour that would occupy him for the rest of his life.

1860 Takes an even longer second trip abroad, visiting Germany, Switzerland, France and Italy, mainly to study educational practices and methods. Death from tuberculosis of his favourite brother Nikolay in southern France, where he had taken him in the hope that its warm climate would halt the disease.

1861 Visits England and Belgium, meeting the exiled Russian revolutionary and publisher Alexander Herzen and perhaps Matthew Arnold in London, and the French socialist Proudhon in Brussels. After his return to Russia, serves as an arbitrator dealing with land settlements on behalf of the local peasantry after the emancipation of the serfs by Alexander II earlier that year. Incurs the resentment of his fellow landowners and is relieved of his appointment.

1862 Starts a soon abandoned pedagogical magazine at Yasnaya Polyana. Police carry out a search of the estate, having been falsely informed that Tolstoy is involved in a radical cabal and in possession of an illegal printing press. Marries Sofya Behrs (b. 1844), the daughter of a prominent physician and neighbouring landowner.

1863 Publishes The Cossacks, a novel based on his time in the Caucasus. Birth of his first child, Sergey. Tolstoy and his wife would have thirteen children – nine boys and four girls – five of them dying in childhood. Starts work on The Decembrists, a novel that would eventually become War and Peace.

1865–6 Serial publication of the first two parts of War and Peace as 1805 in The Russian Herald.

1867–9 Book publication of War and Peace in its entirety.

1870 Works on unfinished novel about the times of Peter I. Reads the plays of Shakespeare, Molière, Goethe, Pushkin and Gogol. Undertakes a study of Greek, beginning with Xenophon and proceeding to Homer and Plato.

1871 While recovering from an alarming bronchial illness in a Bashkirian village in the steppe, east of the Volga town of Samara, continues his study of Greek, reading Herodotus with the help of a local tutor.

1872 Publishes the first version of his Abecedary or Primer.

1873 Begins Anna Karenina. Works on behalf of famine relief in the Samara province where he has bought an estate, describing the conditions there in an open letter to the Moscow News, raising nearly two million roubles on behalf of the afflicted peasants and securing emergency grain allocations.

1874 Much occupied with educational theory. Publishes his New Abecedary and the first part of a companion series, Russian Books for Reading, of more than a hundred brief, simple stories with a clear message.

1875–7 Serial publication of Anna Karenina in The Russian Herald. Appearance of a French translation of his story ‘Two Hussars’ with an introduction by Turgenev in which he declares that with the publication of War and Peace Tolstoy ‘has assumed first place in the affections of the [Russian reading] public’.

1877 Separate book publication of the eighth and last part of Anna Karenina, when Mikhail Katkov, the publisher of The Russian Herald, refuses to print its ‘unpatriotic’ characterization of Russian volunteers in the Russo-Turkish war (1877–8).

1878 Separate publication of Anna Karenina in its entirety. Begins work on an unfinished novel about the era of Nicholas I and the Decembrists, as well as on his long autobiographical essay A Confession.

1880 Works on An Examination of Dogmatic Theology and A Confession.

1881 Writes to Alexander III, exhorting him not to punish the revolutionaries who assassinated Alexander II. Moves with his family from Yasnaya Polyan

a to their new house in the Weavers’ district of central Moscow.

1882 Works on a new translation of the Gospels from the original Greek. Starts his short novel The Death of Ivan Ilyich and his long autobiographical essay What Then Shall We Do?. His passion for languages undiminished, begins a study of biblical Hebrew, taking lessons with a Moscow rabbi.

1883 Finishes his treatise What I Believe. Makes the acquaintance of Vladimir Chertkov, who will play a significant role as his disciple and chief confidant, eventually joining his household.

1884 Family relations become strained. What I Believe is banned by the Russian censors. A Confession is published in Geneva after it, too, is rejected by the censors. Establishes a publishing house (the Intermediary) with Chertkov to produce cheap, edifying literature for the common people.

1885 Writes a number of works for the new publishing venture, including ‘Where Love Is, So God Is Too’ and ‘Strider’ (‘Kholstomer’).

1886 Publishes The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Finishes his play The Power of Darkness and begins his comedy The Fruits of Enlightenment.

1887 Starts work on The Kreutzer Sonata. The Power of Darkness is published, but permission to stage it is refused by the powerful Procurator of the Holy Synod, who objects to its heterodox religious and social views.

1888 Growing friction between his wife and Chertkov. The Power of Darkness is performed in Paris with the help of Émile Zola. Renounces meat, alcohol and tobacco.

1889 Finishes The Kreutzer Sonata. Begins work on the novel Resurrection.

1890 The Kreutzer Sonata is banned from periodical publication by the censor, but is included the next year in the author’s Collected Works. Begins ‘Father Sergius’.

1891 Convinced that personal profits from writing are immoral, renounces the rights to all his works written after 1881. Devotes himself to famine relief in Ryazan province and the surrounding region following widespread crop failures. Helps to bring the neglected situation to public attention and to raise money and organize free food kitchens for the afflicted.

1892 The Fruits of Enlightenment is produced at the Maly Theatre, Moscow.

The Death of Ivan Ilych

The Death of Ivan Ilych Anna Karenina

Anna Karenina Resurrection

Resurrection Family Happiness

Family Happiness War and Peace

War and Peace The Cossacks

The Cossacks The Kreutzer Sonata

The Kreutzer Sonata A Confession

A Confession The Kingdom of God Is Within You

The Kingdom of God Is Within You Father Sergius

Father Sergius Childhood, Boyhood, Youth

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth Lives and Deaths

Lives and Deaths The Devil

The Devil The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Master and Man

The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Master and Man The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy (25+ Works with active table of contents)

The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy (25+ Works with active table of contents) Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (Penguin ed.)

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (Penguin ed.) The Power of Darkness

The Power of Darkness Android Karenina

Android Karenina Family Happiness and Other Stories

Family Happiness and Other Stories The Lion and the Puppy

The Lion and the Puppy Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 2

Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 2 Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 1

Collected Shorter Fiction, Volume 1